Your skin: The new frontier in microbial medicine

This story is brought to you by Azitra, a preclinical stage biotechnology company combining the power of the microbiome with cutting-edge genetic engineering to treat skin disease.I try not to laugh as Dr. Armpit carefully swipes -- and tickles -- my armpit with a large swab. I am a participant in his latest study to determine the factors that affect the microbes living on our skin -- and how those microbes contribute to our body odor. Dr. Armpit is very clear: body odor is not a disease, it’s a problem with your microbiome.The gut microbiome has become a red hot topic in the last several years, and applications like probiotics and fecal microbial transplants have garnered much attention. But many people are less aware of how important a healthy microbiome is for your skin. Research groups across academia and industry are fervently studying how to leverage skin microbes to improve skin health. Armpit odor is just one example of how skin microbes can go haywire, and we’ll return to Dr. Armpit in a moment. But let’s first take look at how microbial engineering can help with one of the most prevalent skin disorders: eczema.Worldwide, about 10 percent of adults have some form of eczema, and it’s even more prevalent among children. If you or someone you know suffers from eczema, you know how challenging it can be. Scratchy, red skin that cracks and bleeds is not only painful, but can also leave you homebound, embarrassed to show your scarlet splotches in public. Hand and body lotions may offer some relief, while pharmaceuticals are pricey and come with an entourage of side effects.

Related: Exploring the Frontiers of Microbiome and Drug Development

Skin is the largest organ of the human body, and is critical as a first line of defense against pathogens, the sun, wind, and water. Its function is crucial for human health, and it often holds important clues about our health. Skin breakouts can be a sign of a poor diet, food or environmental allergy, or early signs of an autoimmune disease. Blemishes can signal sun damage or cancer. We admire those whose skin “glows with health” and do anything we can to avoid wrinkles as we age. We feel sorry for those whose skin is ravaged by eczema. And, some skin diseases, such as Netherton Syndrome in infants, can be fatal or have life-long health consequences. Billions are poured into the cosmetics and skin pharmaceutical industries each year as we try to optimize the health of this critical organ.

'Bacterial microbiome mapping, bioartistic experiment' by François-Joseph Lapointe, Université de Montréal. Credit: François-Joseph Lapointe, Université de Montréal. CC BYAs we consider the health of our skin, we must take into account the thousands of microbes that call our skin home. These microscopic live-ins eat sweat and give us each our own body odor, attract or repel mosquitos (yes, mosquitos do prefer you to your brother on camping trips), and, most importantly, help keep our skin healthy. For example, Staphylococcus epidermidis helps promote wound healing by inhibiting inflammation and can protect against potential skin pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus. It has also been shown to help with moisture retention when applied topically. But it is likely too simplistic to view individual skin microbes as either good or bad. In most cases, the community as an entire ecosystem is the critical component for the well-being of our skin.More diverse microbial communities — those with a variety of species that contribute a wide array of metabolic functions — are associated with healthier skin. Conversely, unbalanced, or dysbiotic, microbial communities are observed in several skin conditions including acne and eczema, where Propionibacterium acnes and S. aureus, respectively, comprise abnormally large proportions of the skin microbial community.Chris Callewaert, known in the microbiome research community as “Dr. Armpit,” is one of the most active researchers seeking to apply skin microbes in practical ways. As a postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University in Belgium and the University of California, San Diego, Dr. Callewaert is particularly interested in tackling embarrassing body odor through skin microbiome “transplants.” He admits that body odor is not a disease, but emphasizes the psychological impacts it can have, especially on women, who, according to his research, tend to smell better than men but feel more ashamed about their body odor than men.

Your armpit: One of many emerging frontiers in the world of the microbiome. Can we engineer a solution to body odor? Source: Pixabay."We found a way to temporarily solve body odor by means of an underarm bacterial transplant from a family member that does not have body odor,” he tells me. “Treatments on 17 subjects showed that we could shift the underarm microbiome to a better smelling one, which was coupled to a significant improvement in underarm odor, for up to one month.” And Dr. Armpit is not the only one interested in solving the problem of body odor through microbes. There are some microbiome-based commercial products already on the market that claim to reduce body odor and clear up acne and other conditions by re-introducing microbes that purportedly have been eliminated by modern hygiene practices, though many are skeptical, claiming that the supporting science doesn’t yet exist.Others are focused on more clinically relevant applications. Richard Gallo and his UC San Diego laboratory team recently reported the successful design of a personalized probiotic skin cream to relieve the most common form of eczema, atopic dermatitis. Motivated by research revealing dysbiotic skin microbiomes favoring an overgrowth of Staph aureus on individuals with eczema, Dr. Gallo went one step further and found that the skin of healthy individuals contained higher amounts of two Staphylococcus species — Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus hominis — than the skin of eczema patients. These two species not only inhibited the growth of Staph aureus but did so without harming other beneficial members of the skin microbial community. A phase 1 clinical trial in which these two Staphylococcus species were isolated from the skin of patients with eczema and then applied to their skin in the form of a personalized probiotic lotion showed that the lotion decreased Staph aureus on the arms of eczema sufferers. Larger clinical studies are now underway.

Related: Living Medicines: Using Gut Microbes to Treat Disease

Bioengineered bacteria may be another way to tackle eczema and other skin conditions — as well as to maintain healthy skin and prevent the development of disease in the first place. Azitra, Inc., founded by a group of Yale University scientists, has developed a strain of S. epidermidis that in addition to retaining its normal anti-Staph aureus effects also secretes filaggrin, a skin molecule essential for maintaining a healthy skin barrier and preventing loss of moisture in the skin. Azitra scientists envision their bioengineered S. epidermidis successfully treating eczema and other skin conditions, as well as simply supporting and maintaining healthy skin by promoting a healthy, balanced skin microbial community.

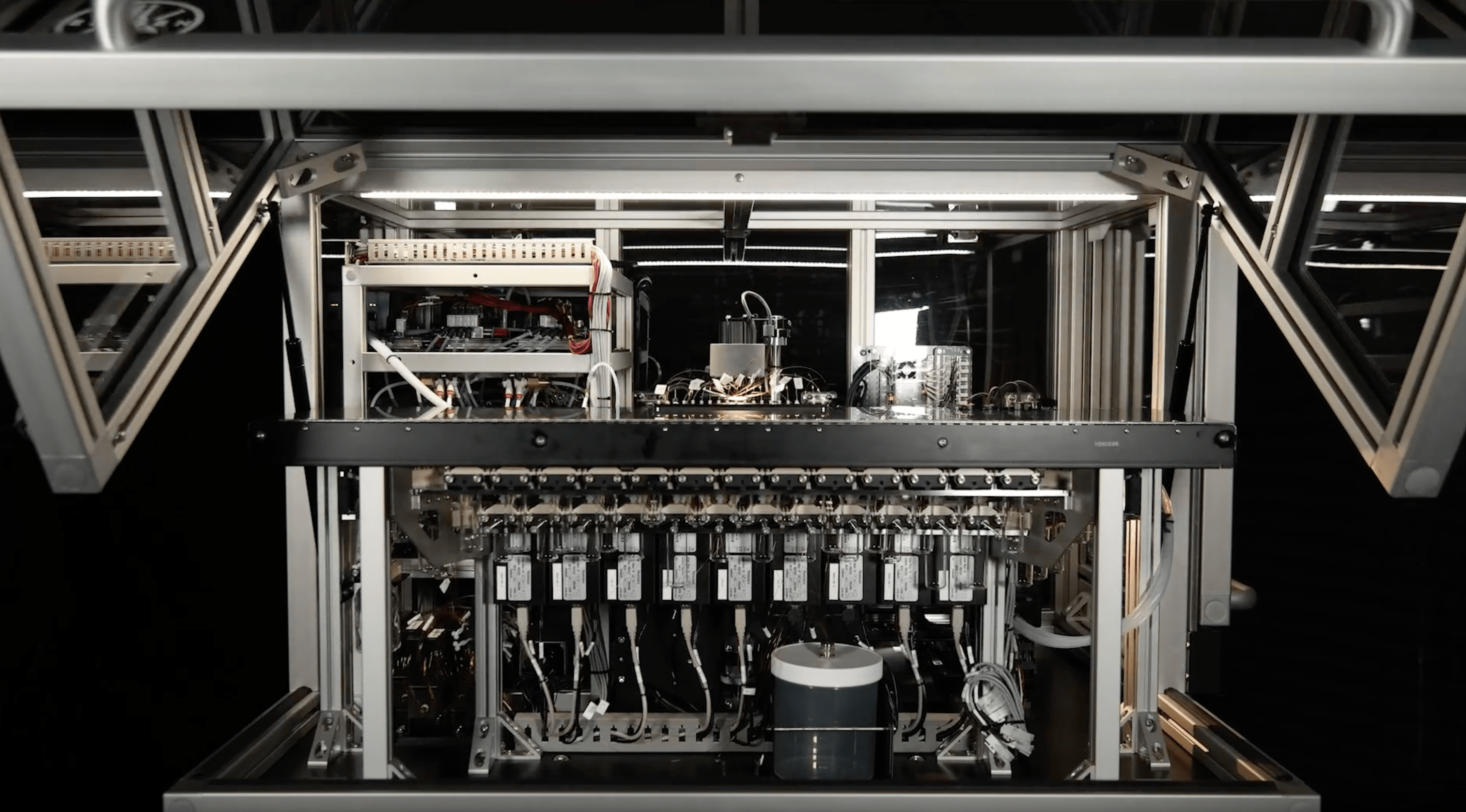

Azitra’s platform for treating skin disease.“Millions of people worldwide suffer from skin diseases with few effective treatment options,” say Travis Whitfill, Azitra Founder and CSO, who will be speaking at SynBioBeta 2018. “We hope to bring forward a novel platform using S. epidermidis to deliver missing proteins as a viable therapeutic strategy for skin diseases.” Azitra is developing an approach to tackle diseases ranging from eczema to rare skin diseases. Their success demonstrates the versatility and importance of a microbe-based platform to treat skin disorders. To meet this vision, Azitra is working with top scientists such as Jackson Lab’s Julia Oh to enhance their platform, with human studies starting soon.

The microbes that live on our skin come into direct contact with myriad things from our environment — toxins, chemicals, other microbes — and they interact with molecules produced by our own cells to help maintain a healthy first line of defense against the outside world. Considering our skin microbes — and how to keep them healthy — as we develop new cosmetics and skin treatments is sure to become a major component of future healthcare.In a world focused on the gut microbiome and how to diagnose and treat disease by targeting the microbes that live in our intestinal tracts, it can be easy to forget just how important our skin and the microbes that live on it are. Researchers like Chris Callewaert, Rich Gallo, the scientists at Azitra, and many others are leading the way into a new frontier of skincare.Don’t miss the “Engineering the microbiome” session at SynBioBeta 2018, The Global Synthetic Biology Summit in San Francisco, October 1–3. Panelists include: Zack Abbott of ZBiotics, Jasmina Aganovic of Mother Dirt, Ted Fjallman of Prokarium, Eugene Joseph of Prime Discoveries, David Kyle of Evolve Biosystems, and Travis Whitfill of Azitra.This story is brought to you by Azitra, a preclinical stage biotechnology company combining the power of the microbiome with cutting-edge genetic engineering to treat skin disease.

.svg)

.png)

.jpg)

.gif)