Engineered Human Therapies

Pioneering Gene Therapy Results Promising for Rare Liver Disease

In a monumental clinical trial, Généthon's gene therapy emerges as a game-changer, turning the tide against Crigler-Najjar syndrome

Aug 17, 2023

Image Generated Using DALL-E

In a world of continual medical breakthroughs, the realm of gene therapy has often been heralded as the frontier of transformative medicine. Today, as we delve into the pages of The New England Journal of Medicine, a groundbreaking revelation emerges. Généthon, a pioneer in the field, has spearheaded a European gene therapy clinical trial that casts a beam of hope for those grappling with Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

This relentless disease, often overshadowed by other conditions, has met its match in the form of GNT 0003. This candidate gene therapy medicine, designed by the brilliant minds at Généthon, intertwines the AAV8 vector with a copy of the gene UGT1A1, a sequence that's been elusive to those with Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

But what makes this discovery truly monumental?

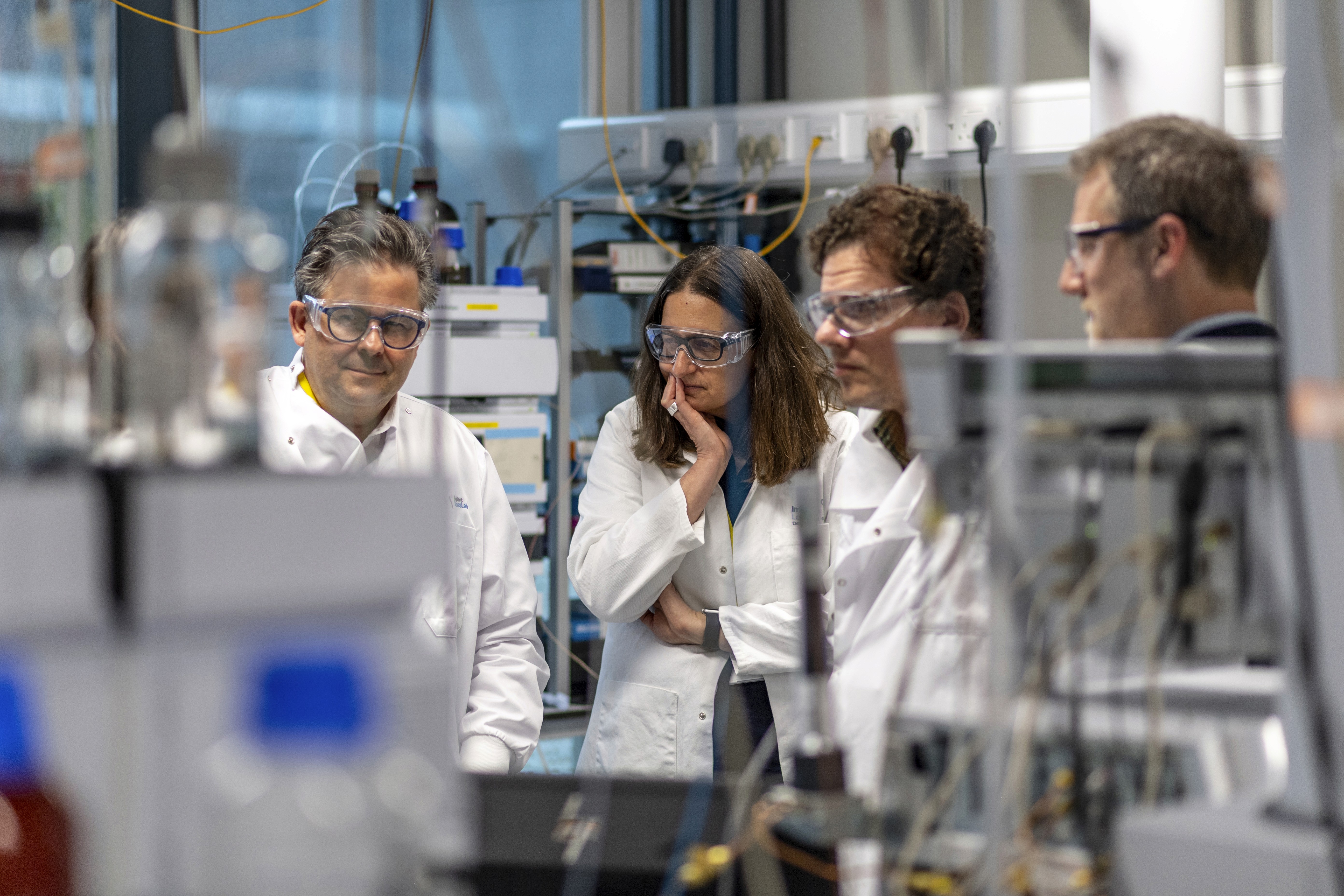

As Giuseppe Ronzitti, the head of Genethon’s “Liver Disease Immunology and Gene Therapy laboratory” passionately puts it, “Genethon’s staff have worked very hard on this project from design to trial, and we are very proud of the results which open the way to treating a large number of other metabolic diseases.”

The trial's objective, conducted hand-in-hand with the European consortium CureCN, spanned across the pristine corridors of renowned European medical facilities. With France, Italy, and the Netherlands at the forefront, the clinical trial, which began in 2017, saw 17 patients bravely stepping into the unknown.

Yet, the results were anything but uncertain.

The therapy's potency is undeniable. With just one intravenous injection, the bilirubin levels plummeted below the toxic threshold. Three courageous patients, after receiving the highest dosage, experienced a life-altering transformation. Phototherapy, once an unshakable part of their routine, became obsolete for 18 months and counting.

But, as with any pioneering venture, safety and efficacy are paramount. The study has, thus far, stood resilient against these tests. The three patients treated with the highest dose showcased a drastic reduction in bilirubin levels, and the results were consistent – the levels stayed beneath the toxic threshold even 80 weeks post-treatment. As Dr. Lorenzo D'Antiga of Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII in Bergamo, Italy, exclaims, "After hemophilia, Crigler Najjar syndrome is the next liver disease treated by gene therapy. In this trial, we managed to restore the synthesis of a non-secreted protein whose deficiency causes severe jaundice in affected patients. We look forward to continuing the next phases of this project and considering also other liver diseases amenable to be cured by our strategy."

The journey, though riddled with challenges, was not undertaken alone. Prof. Dr. Ulrich Beuers of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam graciously acknowledges, “We are most grateful to our participating patients and the whole group of contributors who made these first promising clinical results of our gene therapy trial in Crigler-Najjar Syndrome possible.”

Yet, the odyssey doesn't end here. The pivotal phase, a momentous stage that began last January, seeks to validate these findings in a broader patient demographic, including children aged ten and above. The culmination of this phase could herald a new dawn for Crigler-Najjar syndrome patients, enabling them to access this life-altering treatment, thanks to Généthon’s relentless pursuit of excellence.

As Frédéric Revah, CEO of Généthon, eloquently surmises, “If the results of the pivotal part confirm the efficacy of our gene therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome, we will be able to move on to product license application and making the treatment available to patients, providing them with significantly improved quality of life.”

The horizon of gene therapy gleams brighter today, offering solace and hope to many.