Ginkgo Bioworks and Novo Nordisk are Shifting the SynBio-Biopharma Narrative

Synthetic biology's potential extends beyond faster drug production to the creation of personalized medicines that could bypass traditional manufacturing

Oct 2, 2023

[Tilialucida/Canva]

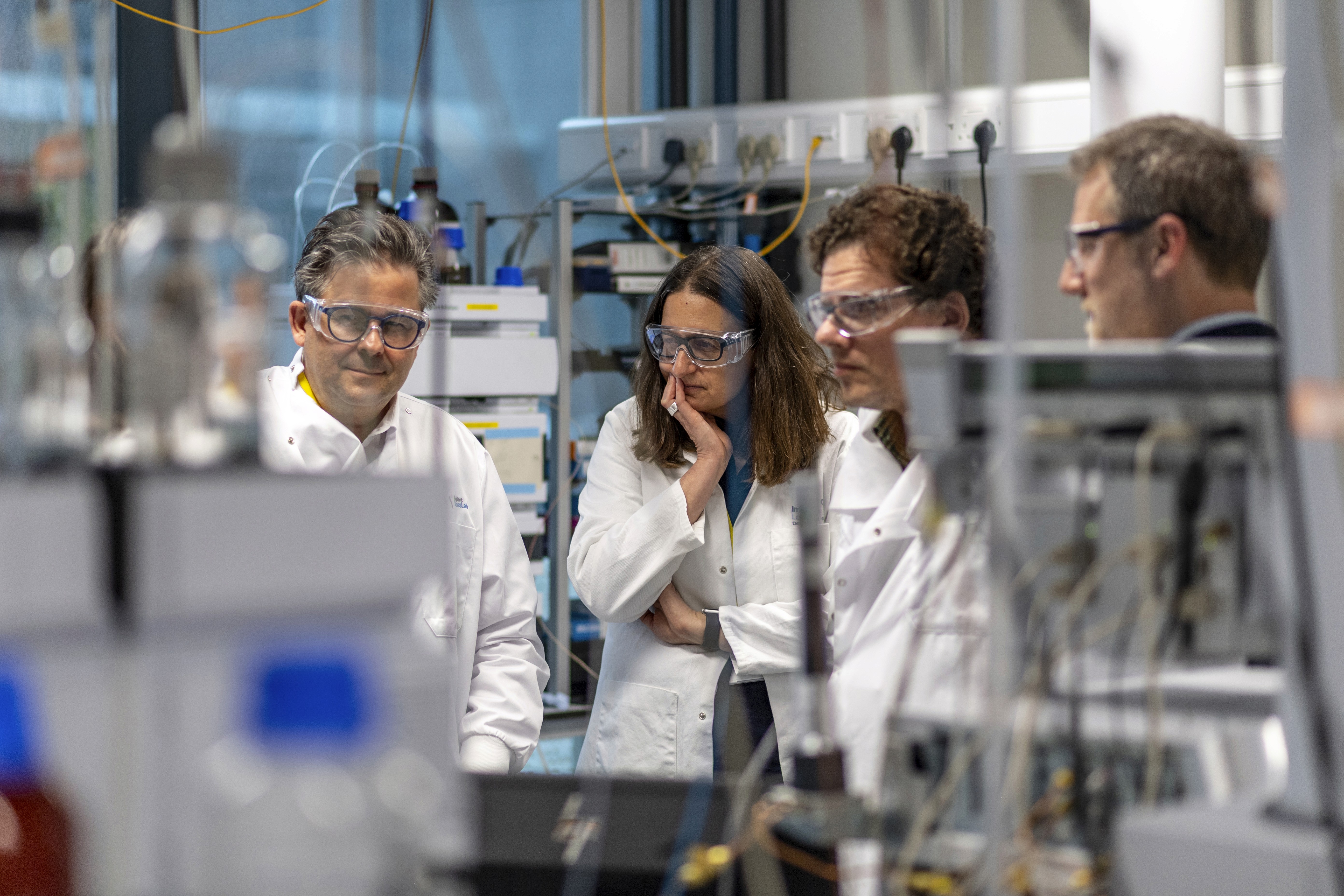

This year marked my first SynBioBeta Conference in four years, and I noticed some big, exciting changes. Most obviously, the central position of biopharma and how synthetic biology can be used by critical industry players to make significant inroads in our fight against diseases of all types. A consensus emerged from the meeting of several brilliant minds, eloquently summarized by Jennifer Wipf, Head of Commercial Cell Engineering at Ginkgo Bioworks:

“Biopharma and synbio are not diametrically opposed like the current narrative portrays. Most of biopharma is doing synbio and has been for a while. The change is using the tools synbio has been using in non-pharma applications and porting them and platforms like Ginkgo over to leverage the synbio work they’ve already been doing in-house in a different way.”

Any doubt about the veracity of this statement should be dispelled by Ginkgo Bioworks’ recent announcement that the company reached a critical milestone in their partnership with top ten pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk: the successful completion of a pilot phase project to create novel microbial expression systems for pharmaceutical products. The companies will now advance into the project’s production phase.

This is an incredible achievement and an important step into synbio and biopharma’s shared future, but the truth is, the groundwork has quietly been laid over the last decade. And in fact, it was at another global leader in pharmaceuticals development—GSK—where the first pieces of the foundation were put into place.

The Art of Making Molecules and Medicines with Enzymes

In 2012, John Baldoni—a pharmaceutical industry veteran with over four decades of experience—was at GSK, encouraging his colleagues to disrupt the pharma industry. They analyzed how drugs were actually being made in the industry, concluding that, by and large, nothing had changed since the late 1800s.

“I asked how we could use molecular biology to make small molecules and how much of our organic chemistry could we replace with enzymatic reactions,” Baldoni said when I sat down with him recently. “The answer turned out to be a very large percentage of our portfolio. We started with a few example projects and then started doing this in earnest. Ultimately, we coupled a number of these reactions together and put them in a microbial system, making a ‘drug in a bug.’”

As a result, Baldoni spearheaded GSK’s synthetic chemistry group, which invested heavily in using enzymatic reactions to simplify the synthetic route to organic molecules and medicines. It didn’t take long for the team to begin adapting the methodology to other application areas.

“When you put something like that in the hands of brilliant people, they start thinking about different ways of using it,” says Baldoni. “They’ve now applied this biosynthetic chemistry paradigm to making other very complex polymers like oligonucleotides. These are things that are not doable using conventional approaches.”

A natural next step in this thought process is applying synbio approaches in drug development. Part of GSK’s success early on was not just their in-house expertise but also the purchase of technology they needed and introduced it into their pipeline. Today, Gingko is the source of a range of technologies for other biopharma companies—like Novo Nordisk—that are taking classically synbio tools and platforms and applying them to pharmaceutical development. Wipf says it's akin to contracting with CROs to do things that the companies themselves don’t want to do, except with Ginkgo, they’re doing things they can’t do.

“We’re a platform of platforms,” says Wipf, explaining that Ginkgo has a broad set of capabilities and tools for tackling a range of different drug discovery and manufacturing challenges. “We think about how to help pharma companies in terms of modalities—cell therapy, gene therapy, gene editing, biologics—and how we can solve problems through a really wide set of tools.”

Sometimes, as is the case with Novo Nordisk, the solution is to use microbes to solve untenable problems. Prokarium is a great example of this approach; the company is using microbes for target delivery in oncology. Other times, the solution may be to use mammalian cells. It all depends on the problem you’re trying to solve, says Wipf.

The Secret Sauce: A Wide Genetic Design Space

Baldoni has seen Ginkgo help tackle a number of such challenges. As a Senior Drug Discovery and Development consultant, he’s worked with several companies that have partnered with Ginkgo to solve critical drug discovery and manufacturing challenges, such as expanding the design space around an already approved adjuvant to create a discovery platform. This is a perfect example of the power of synthetic biology, says Baldoni: rapid generation and testing of compound libraries that can also be leveraged by AI.

“We think about how to bring expansion of the genetic design space together with high throughput testing of those designs to solve what can seem at times intractable,” says Wipf. In this way, the company helps their customers increase their chances of finding the needle in the haystack and finding it faster.

Novo Nordisk is pushing the boundaries by not just trying to find the needle faster. They’re also thinking about how to manufacture their drugs at the outset, tackling scalability earlier in the process by taking multiple parallel approaches to address things like expression and stability. In other words, they’re not just building a better product—they’re building a product that they can actually make.

Medicinal Moonshots

Considering the faster time-to-market and financial savings that will result from increased use of synbio tools in biopharmaceutical production certainly is exciting, for obvious reasons. But we must not forget there is a human side to all of this as well: the patients who benefit from better drugs that they can actually access.

“The kinds of things that synbio is doing—the kinds of things that Ginkgo is enabling through the data that they generate—are going to facilitate an approach that could be hugely disruptive to human therapy. It’s quite remarkable, Baldoni told me. He was talking specifically about personalized medicines and medicines that could even be produced in the clinic, skipping the traditional manufacturing pipeline altogether.

Moonshot? Maybe. But moonshots are what the synbio industry thrives on. And when we aim for them—as Baldoni and his colleagues at GSK did in 2012—we enable ourselves and others to actually make them happen.