Food Agriculture

Cultured Meat Pork’s Out on Sorghum Proteins

Lab-grown pork now features sorghum-based scaffolds for a gluten-free, eco-friendly approach to cultivated meat

Oct 28, 2024

[Grok]

Imagine meat without the animal. It’s not science fiction—this isn’t a scene from Blade Runner. We’re talking about meat, as real as the pork chop on your grill, but engineered in the lab, not harvested from a pig. Cultured meats, often called “clean meat,” have simmered at the edge of the mainstream for over a decade. And now, a few savvy researchers wielding some serious biotech know-how, are cooking up a new breakthrough—one that brings a protein from red sorghum grain into the mix. Yes, sorghum, that hardy grain with a long and peculiar history, is now helping researchers create something akin to pork. And they’re reporting it all in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Let’s pause for a moment. You might wonder, why even bother with cultured meat? Because, like its plant-based cousin, lab-grown meat promises less environmental strain. Growing “meat” in a lab is drastically less land- and water-intensive than raising animals for slaughter, and it emits a fraction of the greenhouse gases. It’s meat without the livestock, without the methane, without the acres of feed crops and sprawling farms. Yet, cultured meat goes a step beyond its plant-based counterparts: these are animal cells, grown on a scaffold, brought to life outside of the animal. This isn’t imitation; it’s cellular mimicry.

The scaffold itself, though, is a prickly challenge. A good scaffold—a kind of skeletal framework for the meat to form on—must be sturdy yet porous, like a sponge for cells to cling to. Over the years, researchers have tried different materials, including wheat gluten and soy protein, but each has drawbacks. Wheat gluten, for instance, presents a problem for those with gluten sensitivities. And many materials dissolve too easily, requiring elaborate preparation. Enter Linzhi Jing, Dejian Huang, and their colleagues, who thought, “Why not try kafirin?”

Kafirin is an obscure protein sourced from sorghum, a grain that’s as drought-resistant as it is fascinating. Sorghum has thrived where other crops fail, and now it might play a role in solving some of the stubborn problems with lab-grown meat. Jing and Huang’s team devised a novel process to extract kafirin from red sorghum flour, then crafted a 3D scaffold by coating sugar cubes in this protein. When the sugar dissolved away, a delicate framework remained—a cubic scaffold that’s gluten-free, insoluble, and stable enough to support growing animal cells.

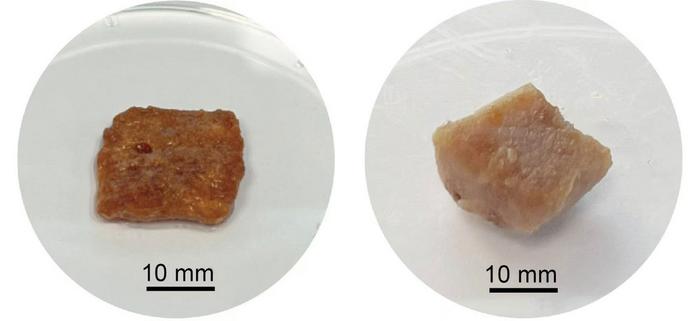

And so, the team seeded this kafirin scaffold with pork stem cells. Within twelve days, something remarkable happened. The cells latched onto the structure, growing and dividing, beginning to resemble actual pork tissue. To be clear, this was no synthetic mock-up: it was real animal tissue, the first step toward lab-grown pork chops.

But here’s where it gets more interesting. The kafirin scaffold, derived from the blood-red sorghum grain, had another curious effect. The red pigments from sorghum imbued the cultured meat with a natural pork-like hue. On a chemical level, sorghum even lent some antioxidant properties to the meat, a little extra nutritional twist that factory-farmed pork could never offer. Yet, there was a side effect. After a round of boiling, the color of the meat barely changed—it was raw pork pink, cooked pork pink, almost as if immune to the flame. It’s a curious phenomenon, likely due to the sorghum proteins’ robust structure, which needs a little more tinkering if we’re to end up with pork that cooks like, well, pork.

For now, this prototype of kafirin-grown meat remains in the research phase, but it’s a tantalizing glimpse of what could be possible. Cultured pork, grown in a lab with a scaffold made of sorghum—tissue spun up in a vessel, almost Frankenstein-like, but with less horror and a lot more sustainability.

One day, you may see this new pork, birthed from the strange marriage of animal cells and ancient grain, resting beside your potatoes. And perhaps that day will mark the beginning of something strange and wonderful, an era where we finally untether meat from the animal.