Engineered Human Therapies

An Exclusive Interview with Helge Bastian About the Uncommon Collaboration Between Foldit, SynBio, and a Confectionery Powerhouse

Dec 19, 2017

What do a confectionery powerhouse, a global biotech development company and a gaming community have in common?A crowdsourcing game. One that might be the key to change the lives of 4.5 million people across the world.Mars, Inc., Thermo Fisher, the University of California, Davis, Northeastern University and the University of Washington announced this past October that they will be joining forces to tackle a global food safety problem: aflatoxin.Like many other biological contaminants, aflatoxin is a naturally occurring molecule that makes its way to our food supply because of lack of proper removal and monitoring methods, as well as under-regulated food manufacturing. Its presence is so prevalent that a recent study in India found that 100% of collected samples of grain flour were contaminated, with an average concentration three times higher than the legal limit allowed in the US. And aflatoxin limits are enforced with good reason: they are known hepatocarcinogens, and 4.5 billion people are exposed to them chronically through the food they eat.There are currently no cost-effective and efficient systems to remove aflatoxins from the food supply. Ideally, one would need an enzyme capable of degrading part of this toxin to decrease or even nullify its toxicity, but the best candidate so far is unable to perform this action. But now, thousands of people are having a go at this problem, restructuring the active sites of the enzyme through the game Foldit.Foldit is a crowdsourcing research platform disguised as a puzzle-solving game. It challenges players to find new structures for proteins exploring how amino acids are folded together, hence the name. The game was first launched in 2008, and had one of its main victories in 2011, when players unraveled the structure of an enzyme involved in a virus similar to HIV.So Mars had the problem, Foldit had a way to reach the solution, but there was something missing: someone willing to produce the hypothetical molecules. This someone became Thermo Fisher.

Uncommon Encounters

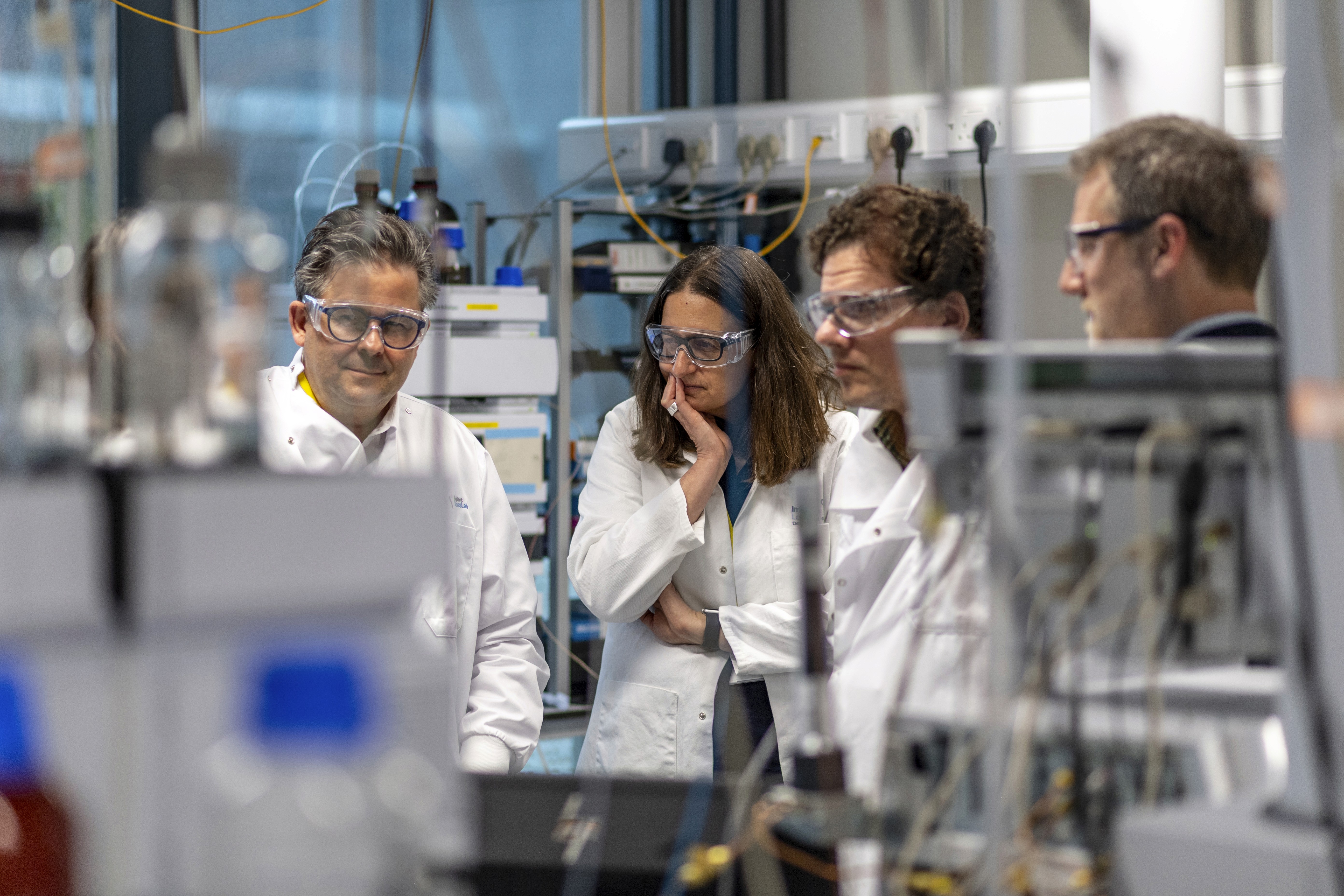

Fold.it has been around for almost ten years, so for Mars and Thermo Fisher to suddenly come in and say “Okay, we want to get in on this game” seems… odd. So how did Thermo get into this?Helge Bastian, VP of synthetic biology at Thermo Fisher, says that this unexpected partnership came to life thanks to the amazing scientific networks that they had in place:“It was due to an interesting connection in the network that we have: Justin Siegel from UC Davis. He’s been a customer for many years of Thermo Fisher, so he knows about our products, services and capabilities. We also have a technical sales specialist in this area, Mary Ann Santos, who’s very engaging with customers, and she came back to me actually and told me that there was this interesting project, and she was wondering if we were the company to participate in that. So this is how it all started, Mary Ann connected me with Justin Siegel, Justin knows Mars for many years, so that’s how the different teams got together.”It made sense for Thermo to jump in as a technical partner, since they had the perfect expertise for the job, but the choice to back a project that wouldn’t generate any profits for the company was still an unusual one. Helge says that this speaks to the core of the company:“Thermo’s mission is pretty simple but very powerful at the same time: It says that we enable our customers to make the world healthier, cleaner and safer. You hear this from every employee, and you hear it a lot, because it resonates so much with both our employees and customers. And if you look at this project, it fits exactly in what we’re working for. We thought it really is about what the company stands for, and also what our capabilities are in the business area I’m leading. It turned out to be a great project to do something for the greater good and not just for us, so it became really interesting for us to dig deeper and see what they had in mind. And of course, in the end we concluded that this is exactly what we stand for and we are happy to support it.”

A Radical Collaboration

So Thermo Fisher became the one in charge of producing the actual DNA that the gamers will hypothesize. Helge explains the pipeline like this:“When people play the Foldit game, Justin Siegel and his team at UC Davis will do the selection of what most likely has the chance to work, and when we know the amino acid sequence of the protein, we will translate it to DNA and optimize it for expression. Then we provide that back to Justin for them to do the proper testing whether this really does have the potential to degrade aflatoxin.”“So, our contribution is making the DNA that encodes for the newly designed enzyme, and that is exactly our expertise: to engineer nucleic acids, which implies designing, writing and manufacturing. And this is for us very scalable, since we can do many genes at a time with many variations.”The role of Thermo as a technical enabler makes it so that there will be as many possibilities tried out as possible, until the best possible solution for the issue emerges. And considering the reach and resources that both Mars, Inc and Thermo Fisher can leverage worldwide, the solution can be made readily available sooner than we think.“What I find interesting,” Helge tells me regarding the project, “is that it’s really two big corporations that are leaders in their fields, but not working in the same field at all. Mars of course is a leader in a slightly different market than us, but through the connections of the research community we realized that Mars once in a while does these projects, goes deeper into the science, and connects with people. So then then the connection came to Thermo Fisher and all of a sudden you have two massive leaders in different industries connecting through science to solve a problem like this, which I think is pretty cool.”

The Other Player(s)

And it’s not just the two leaders: another player that comes into this alliance is literally, a group of players. The self-dubbed Folders, a community of (mostly non-scientists) gamers that attacks the problems laid out in the game, is after all the force that’s providing possible solutions through the game’s puzzle-like interface. Getting non-scientists actively involved in solving scientific problems is a case study on engagement, and can exemplify the reach science has when the public is exposed to it in the best possible way. This engagement, Helge agrees, is a very interesting externality in the project:“That’s a part I really like about it. When I learnt about Foldit, I thought that getting people engaged that are not necessarily scientists in it was really quite nice. It reminds me of a different example where life sciences goes much closer to the consumer, outside of the scientific field. You know 23andme, right? What you see with 23andme is that there’s so many non-scientists that take advantage of it to learn more about themselves, about their DNA and potentially their predispositions and all. I know so many people that do this kind of test. The point being that life sciences really connecting with the consumer is something that’s happening here as well: all of a sudden there is something that people understand, there is a problem out there, and everybody (non-scientists and scientists) can participate in solving it; either in folding the solution protein here, or in the case of 23andme, getting more engaged in their own genetic destiny to understand who they are. And that really seems like a trend in life sciences, going more towards the consumer.”Helge goes further: “I think it’s all about engagement. People need to be willing to look beyond the numbers and making their quarterly results. They have to be open to see where they can support projects that go beyond such business”.

The Initiator

Sometimes, the existence and importance of a problem is obvious for everyone involved, be them researchers, companies, governments. And yet, they remain unsolved. It’s not enough to identify a problem or even a possible solution to it – you need a flag bearer, someone willing to do anything for the cause. In this case, that someone was Howard Shapiro.“Howard is truly the initiator here.” Helge remarks. “He’s been working with Mars for many, many years, and they of course see the problem of aflatoxin every day because of the supply of food they need for their end product. Shapiro is so much about social responsibility, and that reflects on Mars, so they truly go for solving issues that are real issues, and you wonder why nobody has addressed them before.”“So on the one hand it takes individuals that really see these issues and have the passion to solve them independent of whether it does the business well or not. And then you have to have corporations that must understand it’s their responsibility to get engaged in this kind of project. That is exactly what happened here. And I think, without Howard Shapiro who could see this problem and connect to the scientific community, and then running into us, maybe it wouldn’t have worked. It’s probably a little bit of luck that people met each other and were on the same page to address issues as this, and also that it went beyond just business talk: it was responsibility talk. The right people came together, and I think every company can do that if they want to.”And what’s very interesting, is that the final product of the project will be fully open source, not owned by any of the individual companies involved in the development.“It’s really a donation by everyone involved: Mars, us, UC Davis” says Helge. “There’s no IP allowed, it’s completely open source, and if there’s an outcome nobody actually owns that protein. This was a prerequisite from our side and Mars, and it was a very important part of this deal. Otherwise, you wouldn’t even be able to call it a social responsibility project. Whatever comes out of this will be available to the public and anyone can pick it up and use it to make food safer.”

The Power Of SynBio

So the network goes like this: Mars were the ones that were working with the problem, Howard Shapiro was able to pinpoint the key societal issue and bring it forward, Justin Siegel had the expertise and connection with Foldit, Foldit had the way and the people to hypothesize solutions, and Thermo Fisher had the technical tools to enable the solution. A true team effort.“We announced this partnership on October 16th because that’s the date where FAO was founded. It was really neat, well thought through in terms of what we’re doing it and why we were doing it, because it was key for people to understand it.”And really, all the pieces came together, like a (Foldit) puzzle.But besides the obvious testament to the power of scientific networks, Helge remarks that this project is also great proof of the power of synthetic biology to reshape our future.“I think this is a perfect example to illustrate the power of synthetic biology, so we’re trying to accomplish that too: help people understand what synthetic biology can do, not just in the medical area, but in this case to build a safer food supply. This could be a key discipline to build a more sustainable future.”Synthetic biology is, after all, broadening the spectrum of what is possible. So maybe it makes sense that these problems were not solved before, but now they can be.“When new technologies come along, like synthetic biology, the people-- even those that have been in the field for decades-- can look at it and realize that it can be applied to a problem that has been around for much, much longer.” Helge reflects when we wrap up our conversation. “This is why I think this is such a nice example of the value that synthetic biology can be in different areas: People who were not involved in the synbio community at first jump onboard because they see this can be applied to a problem they were looking at from before. So we don’t give up. We consider new technologies to solve what was unsolvable in the past.”